Every deaf person has a story.

The first time I was introduced to this concept, I was a freshman in high school and working on a broadcast journalism project. Honestly, I’d never thought much about deaf culture or American Sign Language (ASL), because I simply didn’t have an interest in it.

Then, one day last year, I noticed my sister having a conversation with a couple of kids at church — only she wasn’t speaking to them. Apparently, my sister had been teaching herself sign language for a couple of months by watching videos online and had actually become quite good at it. When she came back to my family, I was shocked.

“That was actually really cool,” I said.

“Well, you could learn too. I could help you out,” she said.

Around this time in my life, I became interested in the disability community and decided that taking ASL could contribute to a future career in disability or special services law. However, when I brought it up to my adviser, the answer was clear: the political science department wouldn’t accept ASL as a modern foreign language. Not only did this surprise me, but I was also a little offended on behalf of the deaf community.

This isn’t a new topic for Capital administration. It’s a debate that has come up before and was settled by allowing each individual department to decide for themselves. The political science department’s official stance is that it doesn’t consider sign language a modern foreign language. There are more than a couple of problems with this argument.

Let’s break it down:

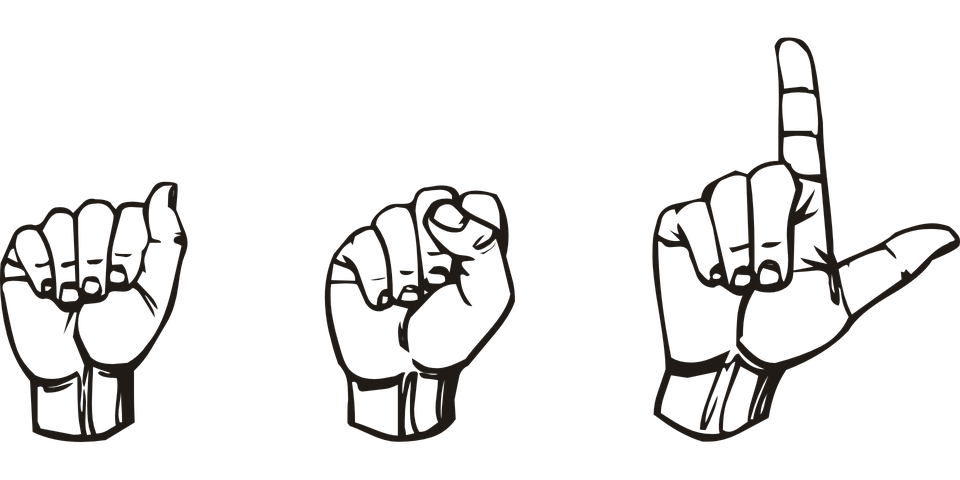

First, American Sign Language is not only a modern language, but it’s also a highly established culture with a history and shared set of values. ASL, even though it is technically English, could easily be considered ‘foreign.’

The word itself doesn’t have to apply to a country and could also be defined as something that is unfamiliar. Able-bodied Americans are usually ignorant to deaf culture simply because they literally lack the ability to communicate and are rarely educated on it.

Second, the implication that ASL is not a language or a culture is incredibly discriminatory and disrespectful of the disability community. Not only is the university not recognizing deaf people’s experiences and voices (or hands, for that matter), they’re also saying that they don’t consider expanding disability awareness important.

Educating students about ASL won’t just increase awareness about deaf people, but also about the shared experiences and realities of living with a perceived disability — the most important part of that sentence being ‘perceived.’

There’s actually a major debate in the community about cochlear implants, because some deaf people argue that their disability simply isn’t one. At the core, this is an argument about whether or not those that are considered ‘disabled’ are disabled at all, focusing on the idea that perhaps the world should be adapting to those who are differently abled instead of the disabled adapting to ableism. This is a different perspective that’s worth hearing, especially at an institution of learning.

Third, there are lots of majors where this could come in handy. Students that are studying anything from special education to medicine could benefit from learning ASL. Not only does it widen their range in normal life, but it opens up job opportunities — especially for anyone interested in education or social work.

Lastly, students with learning disabilities or difficulty learning another language could seriously benefit from ASL. Let’s face it: learning a traditional spoken, written language can be really hard for some students.

While ASL isn’t necessarily easier, it relies on a different set of skills for people who are better at sight learning and physical communication. ASL appeals to a whole different set of students and widens the range of student learning opportunity.

Like I said, every deaf person has a story to tell. I think it’s time that we learn to listen.