An adjunct professor is a teacher who is not on staff, but is hired on a contractual, part-time basis. Typically, they teach the same classes that tenured professors do, but once their contract ends they are not guaranteed a position for next year. According to a National Public Radio article published last year, of all college professors, 76 percent are adjuncts. At Capital, there are over 300.

As a college student, it is not uncommon to spend what little time off waiting tables in order to make enough money to survive. But imagine a happy-go-lucky waitress, called Kim here, who is also an adjunct professor at Capital. She has a second job on the weekends with some of the same college students she teaches during the week.

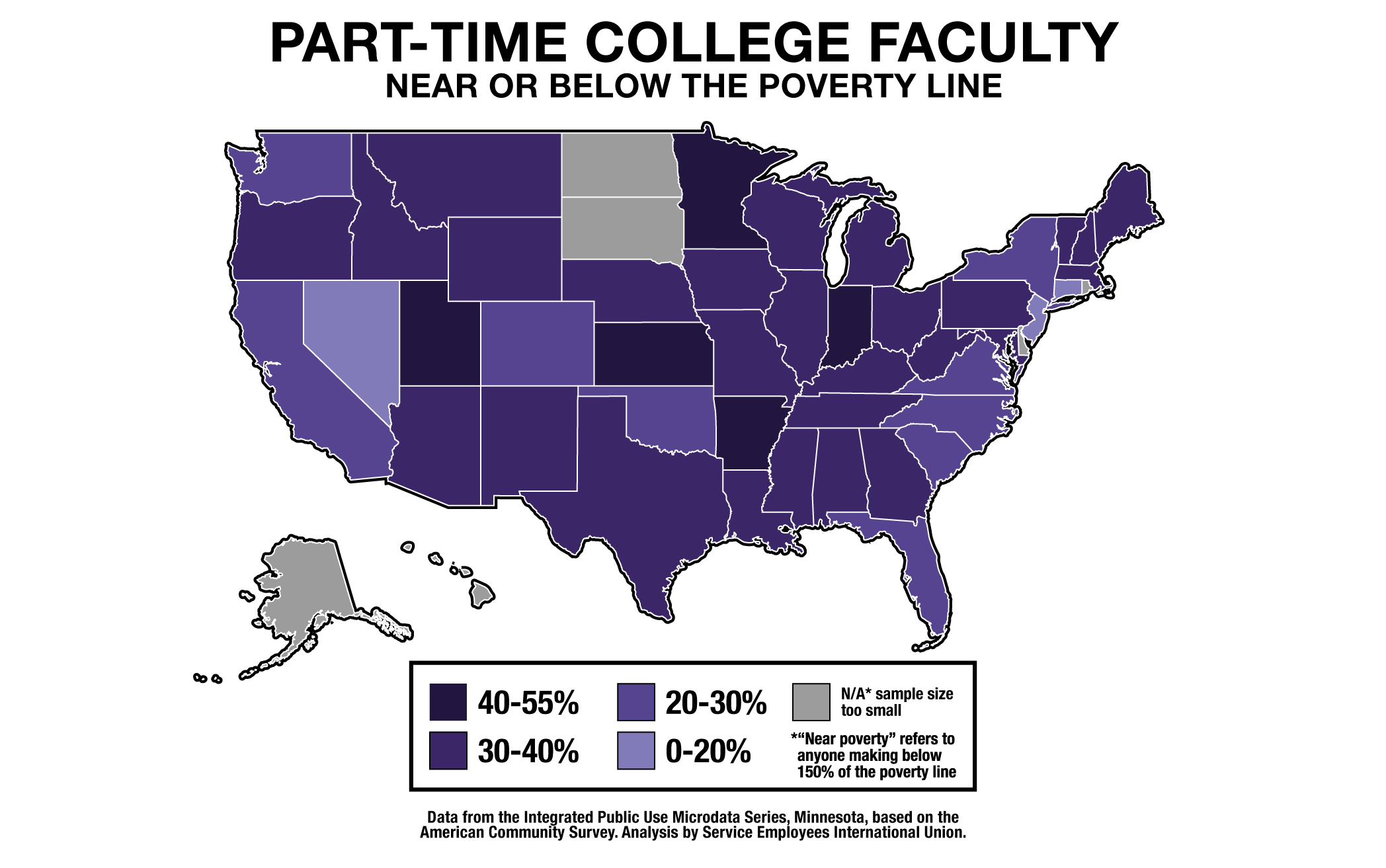

Universities hire adjunct professors in order to reduce cost. According to Glassdoor, an average salary of a tenured professor is $80,000, whereas an adjunct gets paid roughly $2,000 to $6,000 per course. Despite the drastic pay differences, the educational requirements for both positions are exactly the same. This two-tiered system has made it hard for many teachers to live a sustainable life. According to a University of California, Berkeley study, 7 percent of adjuncts are on public assistance, such as welfare and food stamps. In Ohio, 30 to 40 percent of all part time college faculty members are near or below the poverty line.

“I never know if I am ever going to make enough money from semester to semester. I just have no idea,” said Kim.

Kim teaches two courses at Capital, and earns roughly $13,000 a year. Due to the high requirement of education needed to be an adjunct, Kim has over $100,000 in educational loans. Capital does not offer her benefits, and once her contract ends, she is unsure as to whether she will be able to get work. So, in order to provide for her family, she waits tables.

Another adjunct who commented, who will be called Renee, started teaching a few courses at Capital this year.

“In general, adjuncting is fairly nerve-racking, because you never know what the next semester is going to hold,” Renee said.

Renee has a master’s degree and has around $60,000 in debt. She puts around 30 hours of work in each week, and her contract is for $7,500 per semester. Because of low student attendance during the summer, most adjuncts are not able to teach, so that puts her annual income at around $15,000 per year, which is slightly under that of a fast food employee.

“You don’t make much as an adjunct. I’m teaching six classes total and make a third of what a full-time professor makes, for teaching four classes at Capital,” Renee said. “It’s difficult in that sense to live, and to have a family. I never know how many classes I am going to teach per semester.”

However, all of these hurdles do not stop either of these professors from doing what they love.

“I taught at a high school level for two years,” said Renee. “I love the student interaction. I enjoy being in front of students, and watching them improve and grow.”

For them, teaching is not about the money. It is their love of education and their integral part of shaping the lives of students that keeps them in the world of academia.

“People have said, ‘if you won the lottery, would you keep working?’” said Kim. “And the answer is yes, because I love education that much.”

So, the next time that you are in class with an adjunct, and are frantically jotting down notes, secretly thinking to yourself that your teacher is trying to kill you with information overload, remember that they are here because they want to help better your life, even if that means taking on a second or third job just to do it.