Damien Chazelle’s “Whiplash” is brutal.

The film can easily make you feel psychically uncomfortable and leave you ridden with post-traumatic anxiety. J.K. Simmons’s terrifying performance as Terence Fletcher, a verbally abusive, spawn of Satan band director certainly resonates deep into the heart of any college student–especially if you perform music or have had an instructor who has made you cry. But, more important than the movie’s bite, “Whiplash” forces its audience to embrace their own humanity by obliging them to decide what cost must be paid for greatness.

In 1940, legendary drummer Jo Jones threw a symbol at a young Charlie Parker, claiming he had “lost his way and the rhythm section.” Devastated, Parker went home and practiced with all of his being and dazzled the world during his next performance. The flame that Jones had ignited into his belly turned Parker into one of jazz’s most pervasive virtuosos. As Fletcher states in the film, “there are no two words in the English language more harmful than ‘good job.’”

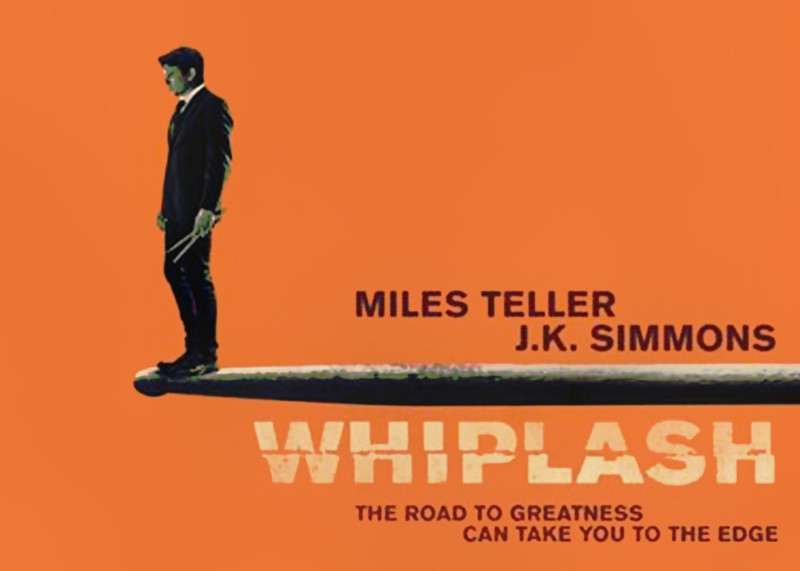

This anecdote and quote by Fletcher conveys the theme embedded in the heart of “Whiplash.” Miles Teller plays Andrew, an awkward, precocious 19-year-old drummer who still spends Friday nights going to the movies with his dad, played by Paul Reiser. Andrew enrolls in one of the most prestigious music academies in the world and soon learns that the price for greatness must be sacrifice, a concept embodied by his dwindling love affair with the wide-eyed theater concession girl, Nicole, played by Melissa Benoist.

“Whiplash’s” only downfall is that it conveys the academic jazz scene as an exclusive boys’ club, which is intensified by Fletcher’s sexually-condescending abuse and infatuation with homosexual ridicule. However, this might simply be Chazelle’s attempt at deconstructing the societal norms we associate with jazz, or to emphasize Fletcher’s inherent misogyny by only choosing boys for his band.

Very rabidly, Andrew falls down the rabbit hole of obsession, as the brutalization brought on by Fletcher simultaneously kindles the primal fire of jazz within Andrew’s soul while transforming him into a fanatical narcissist willing to go to any lengths to impress his instructor–which can only be explained as a jazz-infused Stockholm Syndrome. By juxtaposing visceral imagery, up-tempo swing, and dark humor, “Whiplash” leaves you with an existential analysis of obtaining perfection–how much is too much?